Move semantics: Introduction

Triumph Bonneville T120. Isn’t she beautiful?

I’ve been a full time C++ programmer for a year now. Coming out of college, I thought I knew C++, having extensively practiced DSA (as is the trend nowadays) using the language. After all, I had the syntax for declaring an indexed set memorised! I know, I am not proud of it (now). But I soon discovered, modern cpp is a different beast. What I knew of cpp was a combination of standard C and STL. But there’ more in modern cpp, a lot more.

Today, I’ll write about something that I kind of understood the first time I read it, but not really. After a couple of months, all I had left were doubts. So, I decided to learn the subject properly this time and document my learnings. This article is a result of theory from cpp gods on the internet and my experiments.

What’s the problem?

A few days in, I already got a feeling that making copies of objects is bad. Perhaps because my manager promised me a toffee for each instance of copying that I identified in the codebase, humbly bragging that I wouldn’t be able to (I wasn’t :’)).

The gist of the problem is that we want a way to implement move semantics and perfect forwarding in cpp. What are these and why should you care? Read on to find out.

So, what’s copying?

int x = 5;

int y = x;

Here, x is the name of a memory location in your process’ stack. Compiler initializes this memory location with value 5. y is another memory location which get’s initialized with whatever x is holding. How does the compiler know what x is holding? It uses its symbol table to figure out the address where x lives and copies that value to y’s memory location.

Now, lets’s consider what happens when x’s type is composite, such as a structure.

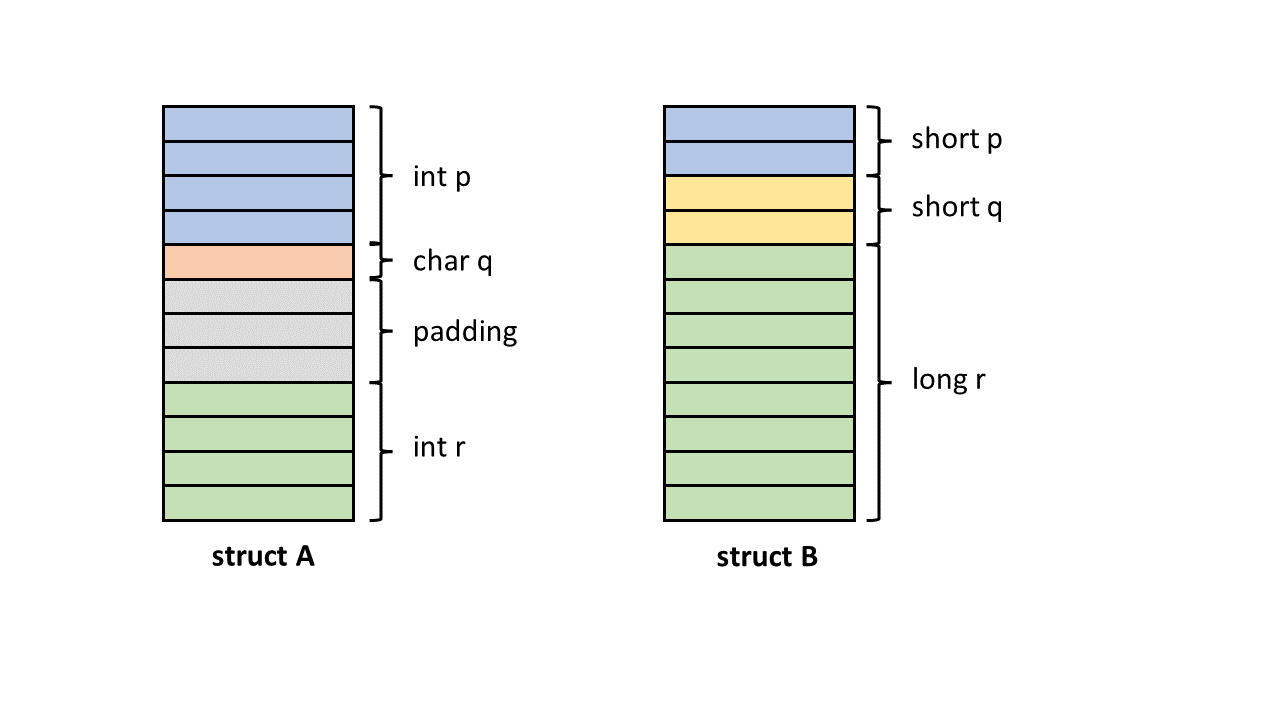

struct A {

int p;

char q;

int r;

};

struct B {

short p;

short q;

long r;

};

A x = {10, 20, 30};

B y = x;

Quick question: what’s sizeof(A), given sizeof(int) is 4, sizeof(char) is 1 and sizeof(long) is 8? Answer

If you answered 9, please have a look at structure aligment. While you are at it, also look at endianness.

Here, x is initialized with x.p = 10, x.q = 20, x.r = 30. y is allocated memory on stack and x’s contents are copied (think in bytes) into y’s memory location.

I encourage you to predict values of y’s members and run the snippet above to find if you were right.

Copy Semantics

How would the same work in case of a class? C++ offers control over how an object can be initialized using Constructor and how it can be copied using Copy Constructor and Copy Assignment operator.

Suppose there’s a class DynamicArray, which holds size n and pointer ptr to a valid contiguous memory location in heap of size n.

class DynamicArray{

public:

size_t n;

void *ptr;

explicit DynamicArray(size_t n) : n(n), ptr(malloc(n)) {

}

virtual ~DynamicArray() {

free(ptr);

}

};

Let’s say x is an object of type DynamicArray, it holds pointer to a memory location with non-zero size. If you trivially copy x to y, the new object will point to x.ptr’s memory. Often, that’s not what we want. We want y to own a new memory location.

Please see this if the keyword

explicitinterests you. The destructor is virtual to allow correct destruction of derived class object if it’s being referred to as base class.

Let’s see a how copy constructor can come to aid.

class DynamicArray{

public:

size_t n;

void *ptr;

explicit DynamicArray(size_t n) : n(n), ptr(malloc(n)) {

}

DynamicArray(const DynamicArray& rhs) : n(rhs.n), ptr(malloc(rhs.n)) { // copy constructor

std::memcpy(this->ptr, rhs.ptr, n);

}

DynamicArray& operator=(const DynamicArray& rhs) { // copy assignment

if (this != &rhs) {

free(ptr); // Clean up existing resource

n = rhs.n;

ptr = malloc(n);

std::memcpy(ptr, rhs.ptr, n);

}

return *this;

}

virtual ~DynamicArray() {

free(ptr);

}

};

rhshere is a const lvalue reference to allow the parameter to be an lvalue or rvalue. We’ll talk about these terms in detail in the coming sections.

It’s left up to the reader to reason about the correctness of the above snippet.

Copy constructor is called when a new object is instantiated using an existing object, whereas copy assignment operator is called when an existing object is overwritten with another existing object.

DynamicArray arr1 = DynamicArray(5); // constructor

DynamicArray arr2(10); // constructor

DynamicArray arr3 = arr1; // copy constructor

arr3 = arr2; // copy assignment operator

Okay, this works. Let’s see what happens when we execute y = x;, where these objects were pre initialized and are of the type DynamicArray.

Two things happen:

- Destructs resource held by

y, in this case, freesy.ptr. - Clones

x’s resources intoy’s resources.

That’s okay if that’s what you want. But consider this:

y = DynamicArray(5);

Let’s understand what happens in the evaluation of this expression step by step:

- A temporary is created as

DynamicArray(5)is evaluated, which allocates resource (5 bytes) once. y’s copy assignment operator is called, where the temporary is referred to asrhs.y’s existing resources are freed up.rhs’s resources are cloned and attached toy.- When the method exits,

rhs’s lifetime is over, so is the temporary’s. Thus, the temporary’s destructor is called where resource allocated in (1) is destructed.

This seems wasteful, doesn’t it? What if the flow looked something like this when the copy assignment operator is called with a parameter that is actually a temporary:

- … same …

- swaps pointers to the this->resource and rhs.resource

- … not needed …

- … not needed …

- … same …

The end result would be the same without the need of an additional copy and destruction.

This scenario was so common, the potential performance benefits so undeniable that the language designers could not ignore it. But, there was no way (prior to C++11) to know whether a function’s parameter was an actual object or a temporary. The designers had to create the concept of rvalue references to solve the problem.

Let’s look at rvalue references next in Part2.

References

[1] learncpp

[2] Thomas Becker’s amazing article

[3] Scott Meyers’ article that made me rage

[4] Performance tests